Mate location

Butterflies tend to have short lives. Females of most species often have less than a week to find a mate, copulate, search for oviposition sites, and lay their eggs. Rapid mate location and recognition are therefore vital – butterflies can’t afford to waste time on fruitless encounters with species other than their own.

Orange tip Anthocharis cardamines, male, Dunsfold, Surrey, England – Adrian Hoskins

Orange tip Anthocharis cardamines, male, Dunsfold, Surrey, England – Adrian Hoskins

Butterflies can see all the colours of the visible spectrum, plus ultra violet. Brightly coloured species such as the Orange tip Anthocharis cardamines are able to detect others of their own kind from several meters away. Experiments with bright blue Morpho species show that waving blue foil in the air is very effective at attracting them towards observers.

Several researchers have attempted to unravel the mysteries of visual communication / recognition in butterflies. Magnus found that males of Argynnis paphia used “paper butterflies” attached to a rotor arm to test the reaction of male Argynnis paphia to numerous variations of colours, shapes, sizes and patterns in paper females. A normal paphia female is dull orange in colour, spotted with black, and has a gentle fluttering flight.

Magnus found however that the “ideal” female, i.e. the paper variant most attractive to the male, was plain orange, up to 4 times the size of the male, and had a very rapid wing flutter-frequency of about 120 Hz. This poses the question – why didn’t female paphia evolve to have huge bright orange wings ?The answer is probably that the normal spotted female has sufficient orange content to attract the male, while a plain orange female would be too conspicuous to predatory birds.

A spotted pattern is an effective camouflage, given that the female spends the most important part of her life i.e. the oviposition stage, fluttering around in the dappled sunlight of mature woodlands. A plain orange female would attract males more easily, but would quickly be found by birds, and would not live long enough to lay her eggs.

Papilio machaon – a species with an instantly recognisable pattern – Adrian Hoskins

While wing colour is important in the initial stages of mate location, pattern recognition is a different matter, and only comes into play when the butterflies are in close proximity. Conspicuous patterns such as the black and yellow pattern of Papilio machaon, or the black, red and white of Vanessa atalanta may be recognised at close distances, but it is obvious that subtle patterns cannot be.

To illustrate this point, simply imagine an alpine meadow with a mixed population of Erebia species. All are very drab brown insects of similar size and shape, differing only in minute details that could not possible be seen with the poor resolution of a butterfly’s eyes. The same argument applies to the Pyrgus skippers, the Melitaea Fritillaries and the numerous Polyommatine blues, where many very similarly patterned and closely related species share the same habitat.

If butterflies relied solely on visual stimuli for mate recognition they would waste almost all of their short lives chasing after the wrong species, and reproduction success would be very low indeed.

Mate recognition

During the initial “approach” phase of mate location males will chase after almost any small moving object including falling leaves, bees, and butterflies of any species and either sex. After this initial contact, follow up behaviour depends on the response of the chased object. Birds are avoided but other butterflies are always investigated, using a combination of visual and chemical cues.

Ultra-violet patterns on the wings often enable butterflies to recognise their own species. When butterflies get close to each other they use chemical messaging, in the form of pheromones, which provides additional confirmation of species, and tells them whether they are of the same or opposite sex.

If the pheromones indicate that the object being pursued is a conspecific male, the butterflies are often stimulated into aerial dogfights in which they battle for ownership of good vantage points from which to intercept passing females. These territorial battles can last for several minutes, after which one male is ousted from the vicinity.

Alternatively, if the pheromones indicate that the object being pursued is a conspecific female, the male is stimulated into initiating courtship. In many species exposing a female to male pheromones is enough to initiate instant copulation, but in other species a complex courtship ritual involving a protracted series of visual, tactile or olfactory stimuli and responses is necessary before copulation can take place.

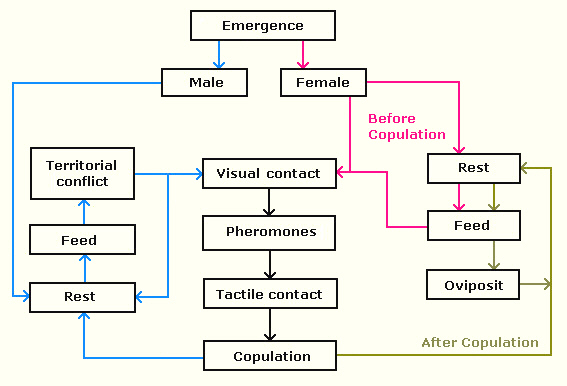

Flowchart : behavioural cycle of a typical butterfly

Pupal mating

In the genus Heliconius most species rely entirely on airborne chemicals to locate mates. Males of hecale, ismenius and cydno are attracted by pheromones to the pupae of conspecific females. The day before emergence a female pupa will usually have several males in close attendance. A frantic battle takes place the instant she hatches, as the males all struggle to copulate with her, not even allowing her time to expand and dry her wings.

In some other Heliconius species such as hecalesia, hewitsoni, erato, charithonia and sara the males don’t even wait until the female emerges. Instead they physically break open her pupa and copulate as soon as her genitalia are accessible.

Androconia

Males of Satyrinae, Hesperiinae, Pyrginae and Theclinae have specialised scales on their forewings called androconia. These have sacs at their bases containing pheromones which they disseminate into the atmosphere via tiny hairs or plumes on the edges of the scales. The pheromones are used to attract females and entice them to copulate.

In Danainae the androconia are on the hindwings. The males have tufts of hair-pencils at the tips of their abdomens which they brush against the androconial scales to collect pheromones. These are later disseminated by expanding the tufts when in the presence of females.

Males of several Ithomiine species gather at “leks”, where they release pheromones from hair-like androconial scales on the upperside hindwings. These attract more males, which release further pheromones. After a few days a lek may include a dozen or more different Ithomiine species. Passing females are attracted by the complex fragrances, and their presence stimulates the males to open their wings and release further pheromones that entice the females into copulation.

Courtship rituals

The courtship behaviour of butterflies in general is inadequately studied, but it is clear that in most species the female will not permit the male to copulate until he has completed an often complex ritual. This typically begins with the male releasing airborne pheromones, which leads to the female settling on foliage. The male might then begin a “courtship dance” around the female, whirring his wings to waft his pheromones across her antennae.

If the female accepts his advances ( she may instead give him a rejection signal ), there is often a confirmation ritual in which contact pheromones ( cuticular hydrocarbons ) come into play. A well known example is the Grayling Hipparchia semele, in which the male clasps the females antennae between his wings to bring them into direct contact with his androconial scales. The Orange Sulfur Colias eurytheme behaves in exactly the same way.

Another example is the Wood White Leptidea sinapis, in which the male and female sit on a leaf, facing each other, exchanging chemical messages with their antennae. The male repeatedly flicks out his long proboscis, whipping the female alternately on the underside of her left and right wings. Both sexes periodically flick open their wings. The butterflies are clearly communicating something but the ritual does not appear to instigate copulation, so the nature of the “messages” is unclear.

Wood Whites Leptidea sinapis engaged in courtship ritual – Adrian Hoskins

Small Tortoiseshells Aglais urticae have a protracted courtship which can last for several hours. The male follows the female as she flies from place to place. When she settles and opens her wings, he walks onto her hindwings, tapping them with his antennae. The process is repeated numerous times over several hours, during which the male will drive off any other intruding males. Eventually the female leads him to a sheltered spot, typically beneath a small bush, where copulation takes place.

Brimstone Gonepteryx rhamni males are also commonly seen “wing-walking” on females, but this is invariably followed by the female inverting her wings and raising her abdomen – a signal to the male that she is rejecting his advances, and a sign that she has already mated ( females of most butterflies only mate once ).

Brimstone Gonepteryx rhamni, female raises abdomen to signal rejection to male – Adrian Hoskins

When female Brimstones are receptive, copulation takes place almost instantly, without any observable pre-nuptial ritual. Most butterflies remain copulated only for an hour or so, but the Brimstone is quite remarkable in this respect – I once found a pair of Brimstones which remained copulated beneath a bramble leaf for an amazing 17 days before finally parting company !Males usually mate with several females in the course of their lives.

Females of certain long-lived species such as the Monarch Danaus plexippus will mate with several males, but in the majority of species females normally only mate once. After mating, the genital opening on the females of Marsh Fritillaries Euphydryas aurinia and some other species becomes sealed, physically preventing them from mating with other males. Males of the Apollo butterfly Parnassius apollo seal the female genital opening with a structure called a sphragis to prevent other males from copulating.

In the case of species which hibernate as adults, copulation occurs in the spring. Brimstones for example emerge in July, feed for a few weeks, and then go into hibernation for several months. After awakening the following April, they are mated, and then the females fly many miles, often across inhospitable terrain, stopping to lay their eggs on any buckthorn plants that they encounter on their travels. The butterflies thus spread throughout the countryside, interbreeding with other Brimstones that may have originated a considerable distance away.

The resulting high genetic diversity is probably a major factor in the remarkable success of the species, which is able to exploit an enormous range of habitats and climatic extremes, being found at altitudes from sea level to 2800m, and having a range that encompasses north Africa, the whole of Europe, and extends across temperate Asia to Siberia and Mongolia.

Perching, patrolling, and territories

Entomologists have traditionally divided the pre-nuptial behaviour of butterflies into two groups – those that “patrol” and those that “perch”.

Patrolling species are those where the male actively patrols a regular or random route through it’s habitat in order to locate a female. Perching species are those where the male spends long periods sitting on a prominent projecting leaf, or on a particular rock or patch of ground, which it uses as a vantage point from which to intercept passing females. These vantage points form the bases of territories, which the males will vigorously defend against other intruding males.

If two males meet, they twist and turn around each other in the air, and end up spiralling upwards to a great height until the “intruding” male ( usually a newly emerged individual which has not yet found it’s own perch ) is ousted from the territory.

A perch is simply a vantage point from which males can get a good view of all passing insects. Each species has it’s own preferred type of perch however – the Purple Emperor Apatura iris will perch at the top of a prominent tree, usually on a hilltop, while the Duke of Burgundy Hamearis lucina will perch on the leaf of a bush, typically in a small glade or at the sunny intersection of forest paths. In both cases the butterflies have homed in on a spot where they have a good view in all directions, and can survey and intercept passing females.

In practice, any male, of either a patrolling or perching species, will intercept any other flying insect of similar size and colour, to investigate it and determine whether it is a female of it’s own species. Most males will try to fly over or around a female in a particular direction. A Silver-washed Fritillary male for example will loop over and under a female as she flies along a track, showering her with pheromones. A Silver-spotted Skipper male on the other hand will perform a figure of eight dance around a settled female, whirring his wings to waft pheromones over her antennae.

Lysandra bellargus copulating pair ( female on left ) – Adrian Hoskins

Lysandra bellargus copulating pair ( female on left ) – Adrian Hoskins

Lekking

In South American rainforests and cloudforests male Glasswings and Tigers ( Ithomiinae ) often gather at ephemeral “leks”. It usually takes about 3-7 days for a lek to form, and it may exist for up to 3 months, during which time numerous individual males will come and go.

At the leks males release pheromones from hair-like androconial scales on the uppersides of their hindwings. These pheromones attract more males, which release further pheromones. After a few days the lek may contain between a dozen and several hundred individuals, comprised of up to 20 or 30 different Ithomiine species.

Passing females are attracted to the leks by the complex fragrances. Their presence stimulates the males to open their wings and release other pheromones that entice the females into copulation.