The Linnaean System

Before the advent of scientific nomenclature, confusion reigned :

Example 1 – The butterfly known in Britain as the Camberwell Beauty has in past times been called the Grand Surprise, the Willow Beauty and the White Petticoat. In the USA it is called the Mourning Cloak. In Europe it has common names in several different languages.

Example 2 – The two butterflies known to early entomologists as the Selvedged Heath Eye and the Golden Heath Eye were later discovered to be the male and female of a single species which was initially called the Gatekeeper but is now called the Small Heath. The original name Gatekeeper is now applied to an entirely different species which has variously been known as the Hedge Brown, Hedge Eye and Large Heath. The name Large Heath however is now used for an entirely different species that was previously known as the Manchester Argus, or Marsh Ringlet !

The Swedish naturalist Carl von Linnaeus ( Carolus Linnaeus ) decided to put an end to this confusion. He realised that an internationally recognised name was needed for every creature and plant, and that every organism should be classified according to it’s relationship with other organisms. In 1735 he launched the Systema Naturae, a catalogue of the names of all known animals and plants. Later, in 1758 came the 10th edition of Systema Naturae, which is regarded as the starting point for the current system of classifying animals and plants by family, genus and species.

Originally Linnaeus placed all butterflies and moths in the same genus Papilio. Later it was realised that there was a need to divide this genus, so as to distinguish groups with different characteristics. Since the time of Linnaeus many thousands of new species have been discovered and described by scientists, and hundreds of genera have been created to accommodate them.

Every known taxon is designated a binomial ( two-word ) name derived from Latin or Greek roots. An example is the Common Blue butterfly Polyommatus icarus :

The Common Blue was designated by Rottemburg in 1775 as Polyommatus icarus. The first part of the name means ‘many spotted’. It refers to the distinctive markings on the underside of the wings of all species in the genus Polyommatus. The name icarus refers to a character in Greek Mythology. According to legend Icarus and his father Daedalus were imprisoned in the Labyrinth with a terrible creature, the Minotaur. In order to escape, Daedalus fashioned a pair of wings for himself and his son, made of feathers and wax. Before they took off from the prison, Daedalus warned his son not to fly too close to the sun. Icarus unfortunately became so overcome by the excitement of being able to fly that he forgot his father’s warning. He got too close to the sun and his wings melted. He then fell into the sea in the area which now bears his name, the Icarian Sea near Icaria, an island southwest of Samos.

Scientific names should always be written with the genus, species and subspecies italicised, then the author’s name and the date the description of the taxon was first published.

Thus the Common Blue is called : Polyommatus icarus icarus ROTTEMBURG, 1775

The taxonomic hierarchy

The Linnaean System divides the Animal Kingdom into groups called phyla. The phylum Arthropoda i.e. those animals with jointed limbs and a hard exoskeleton, is divided into several classes. Among these are the Crustacea which includes crabs, lobsters, shrimps & woodlice. Other classes include Chilopoda ( centipedes ), Diplopoda ( millipedes ), Arachnida ( mites, spiders & scorpions ) and the Insecta ( insects ).

The class Insecta includes over 75% of all animal species. It is divided into several super-orders, one of which is Amphiesmenoptera.

The latter is split into 2 orders – Trichoptera ( caddisflies ) and Lepidoptera ( butterflies & moths ). These 2 orders share a common ancestor, Necrotaulidae, and have many features in common, e.g. their wing venation is fundamentally similar, their wings are covered in setae ( modified to form scales in Lepidoptera ), and their larvae have mouthparts with structures and glands modified to produce silk.

The table below shows Polyommatus icarus in relation to the rest of the Animal Kingdom :

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animals |

| Phylum | Arthropoda | Joint-limbed invertebrates |

| Class | Insecta | Insects |

| Sub-Class | Endopterygota | Insects with a 4 stage lifecycle : ova / larva / pupa / imago |

| Superorder | Amphiesmenoptera | Trichoptera ( caddisflies ) & Lepidoptera |

| Order | Lepidoptera | Butterflies, moths & skippers |

| Sub-Order | Ditrysia | A division based on genitalia characteristics |

| Super-Family | Papilionoidea | Scudder butterflies |

| Family | Lycaenidae | Gossamer-winged butterflies |

| Sub-Family | Polyommatinae | Blues |

| Tribe | Polyommatini | Ciliate Blues |

| Sub-Tribe | – | no sub-tribe has been allocated for the genus Polyommatus |

| Genus | Polyommatus | Many-spotted Ciliate Blues |

| Sub-Genus | – | no sub-genus has been allocated for the species icarus |

| species | icarus | Common Blue |

| subspecies | mariscolore | Irish sub-species of icarus |

| Author | ROTTEMBURG, 1775 | the taxonomist who described the species |

Lepidoptera

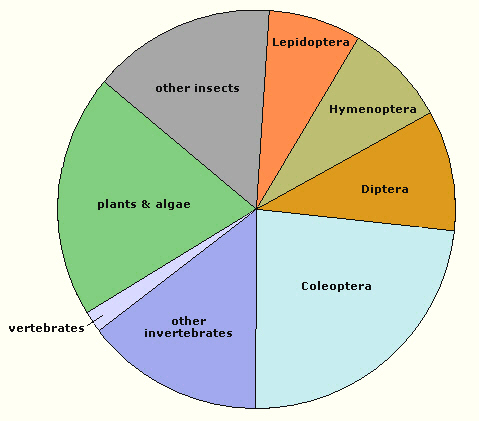

About 7% of all life forms on Earth are members of the Order Lepidoptera – the butterflies, skippers and moths ( indicated in orange ) :

The Lepidoptera comprises of about 174,250 known species ( this only represents a fraction of the species in existence, as many more await to be discovered and described, especially among the tropical “micro” moth families ). The classification of Lepidoptera is under constant revision, but they are currently divided into 126 families, 7 of which are colloquially known as butterflies :

| Family | subfamilies |

| Hesperiidae | Heteropterinae, Hesperiinae, Pyrginae, Pyrrhopyginae, Megathyminae, |

| Coeliadinae, Trapezitinae | |

| Papilionidae | Papilioninae, Parnassiinae, Baroniinae |

| Pieridae | Pierinae, Coliadinae, Dismorphiinae |

| Lycaenidae | Lycaeninae, Polyommatinae, Theclinae, Curetinae, Poritiinae, Miletinae, Lipteninae, Liphyrinae |

| Riodinidae | Riodininae, Euselasiinae |

| Nymphalidae | Nymphalinae, Satyrinae, Morphinae, Charaxinae, Apaturinae, Limenitidinae, |

| Biblidinae, Cyrestinae, Heliconiinae, Danainae, Libytheinae | |

| Hedylidae | Hedylidae – ‘moth butterflies’ are not divided into subfamilies |

Butterflies by day and moths by night ?

It is wrong to think of butterflies and moths as being different. The families which we call butterflies are generally those with brightly coloured day-flying species. There are however hundreds of moths among the families Zygaenidae, Arctiidae and Uraniidae which are also brightly coloured and day-flying. Conversely there are many butterflies among the Hesperiidae, Satyrinae and Brassolini that are very dull and inconspicuous, and would be dismissed as moths by most people.

Another “fact” often quoted is that butterflies always have clubbed tips to their antennae, but that moths never do. The colourful day-flying Zygaenidae moths however do have swollen tips to their antennae, and the huge day-flying Cane-borer moths ( Castniidae ) possess clubbed antennae just like those of butterflies!

Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that many butterflies fly at night as well as during the day, particularly in the tropics. Examples include the Caligo Owl butterflies, Melanitis Evening Browns and certain Riodinids. Examples from temperate regions include the Red Admiral Vanessa atalanta and the Monarch Danaus plexippus both of which regularly fly into moth traps in the middle of the night.

The 35 species of the family Hedylidae are nocturnal and moth-like in appearance. The early stages however have many butterfly-like characteristics. The eggs for example are structurally closer to those of Pieridae and Nymphalidae than to moth eggs. The caterpillars have horn-like processes like Apaturinae, a bifid tail as found in Satyrinae, and secondary setae as found in Pieridae. They also have an “anal comb” used for expelling droppings – a characteristic of the Hesperiinae. The pupae likewise have structural characteristics more representative of butterfly pupae, and are secured to the substrate with a silken girdle, just like those of the Pieridae and Papilionidae.

Taxonomic revision

Taxonomy is not an exact science. It relies on suppositions about the relationships between various species, and about their evolutionary ancestry. Because of this, the classification ( and the scientific names ) of butterflies and moths are under constant revision.

New techniques such as microbiology, phylogenetics, DNA sequencing, and the study of larval morphology regularly shed new light on the relationships between species. This increasing knowledge regularly results in the necessity to revise classification. Sometimes it is a simple matter of relocating a species to a different genus. On rare occasions however it may require that a genus, tribe or even an entire subfamily be migrated from its familiar home and relocated into another family or superfamily.

The inexact nature of taxonomy, and the fact that it relies on opinion rather than fact, unfortunately means that scientists often find themselves in disagreement about which genus a particular species belongs to, or whether two or more butterflies with very similar characteristics should be classified as separate species or as subspecies.

Occasionally a taxonomist will believe that he or she has discovered a “new to science” species and will describe it’s characteristics and publish a name for it. Later however they may realise that the species has already been described and named by someone else. In such cases the oldest name takes precedence, and the newer name is discarded, and listed as an invalid ( junior ) synonym.

| The reclassification of Bia actorion As our knowledge grows and relationships between different taxa are more clearly understood it sometimes becomes necessary for a butterfly to be reclassified under a different genus, or even under a different subfamily or family. One of the most well known examples of this phenomenon is Bia actorion, a neotropical species originally described by Linnaeus in 1763 as Papilio actorion and placed in the then all-embracing family Papilionidae. During the next few years as many more species were discovered it became clear that a single genus was inadequate. It was ordained that the original genus Papilio should be used exclusively for Swallowtail butterflies, and that new genera would need to be created to house all other species. Consequently in 1819 Hubner created the genus Bia to accommodate actorion. Hubner believed that actorion was related to the “Browns” of Europe, so he placed Bia in the Satyridae, which was then regarded as a family of equal rank to the Nymphalidae. In the 20th century Wahlberg and other taxonomists concluded that the Satyridae, Brassolidae, Amathusiidae, Acraeidae, Heliconiidae etc all shared a number of common characteristics, and that they should thus all be relegated to become subfamilies of the Nymphalidae. For a few years Bia actorion – also known for a while as Napho actoriaena – was retained in the Satyrinae, but further studies determined that it really belonged to the Brassolinae. Currently Bia actorion and it’s close relative Bia peruana are classified as members of the subtribe Biina, which is placed in the Brassolini – a tribe within the Morphinae, which is now considered to be a subfamily of the greatly enlarged Nymphalidae ! |

How scientists describe and name new species

When someone thinks they’ve discovered a new species, they have to provide sample specimens to taxonomists for analysis. By comparing the structure of the wing venation, genitalia and various other anatomical features to that of currently known species, taxonomists can then easily ascertain the genus, and decide whether the specimens represent a previously known species or a new one.

If there are significant differences between the new species and all previously known species it may be regarded as sufficiently unique to deserve the creation of a new genus. If on the other hand its anatomy is close to that of other species it will be placed in an existing genus, and will be allocated a new species name in recognition of its uniqueness.

New species are given a Latinised name and a full scientific description, which are published in a recognised scientific journal.

The origin of scientific names varies enormously. Some species are named after Greek gods, some are named after the place where the butterfly was discovered or named in honour of some eminent entomologist. Names can also be descriptive of the colour, pattern or wing shape.

The Charismatic Metalmarks

Taxonomists are not usually renowned for having a great sense of humour, but amongst their more hilarious moments they have colluded to provide us with some entertaining scientific names. Hence there are a pair of metalmarks from Colombia, named by Hall & Harvey in 2002 as Charis ma and Charis matic. Both have now been renamed rather less attractively as Detritivora ma and D. matic. The new genus name refers to the fact that the larvae feed on decaying leaves and other detritus on the forest floor.

The world’s most dismal butterfly ?

Sometimes it can be difficult to think up names for some of the more mundane looking species, particularly for the hundreds of near-identical dull brown skipper species found in the neotropics. In 1997 Austin was apparently so totally unimpressed with his latest discovery that he gave a new Mexican species the unfortunate name Inglorius mediocris, which needs little translation !Below is an example of a scientific description :

|

**Inglorius Austin, new genus**

**Type species: Inglorius mediocris Austin, new species** **Description:** Palpi are slender, with the third segment straight, protruding well beyond the second segment and approximately equal to the length of the dorsal edge of the second segment. Antennae are long, extending beyond the end of the forewing discal cell, nearly 60% of the length of the forewing costa. They are black with a pale ochreous color beneath distally and below the club. The club comprises just over 1/4 (28%) of the antennal length, bent to an apiculus at its thickest part, with the apiculus length about 2 times the club width. The club is nudum grey and consists of 12 segments (3 on the club, 9 on the apiculus). The forewing discal cell is slightly produced, approximately 75% of the length of the anal margin, with the origin of vein CuA2 nearer to CuA than to the wing base. The hindwing discal cell is just over half the wing width. The mid tibiae have four fine spines on the inner surface and a single pair of spurs, while the hind tibiae have two pairs of spurs. The forewing is produced with a slight concavity between CuA1 and 2A. The hindwing is convex anteriorly and somewhat concave between CuA1 and 2A. There are no apparent secondary sexual characters. **Male genitalia:** The tegumen is short. The uncus is longer than the tegumen, undivided, and hood-like over the gnathos. The gnathos is as long as the uncus, divided, extending laterad of the uncus in dorsal view and as rectangular flaps mesad in ventral view. The vinculum is sinuate, and the saccus is short. The valva is very long, with the ampulla/costa long and sloping somewhat downward caudad. The harpe is long and roughly triangular, ending in an inward-turned point caudad. The dorsal margin is undulate and weakly serrate cephalad. The aedeagus is tubular, with the anterior portion missing, and the caudal end expanded terminally in lateral view. There is no apparent cornutus. |

More ‘creative’ species names

The entomologist Burns was clearly having a mental block when it came to naming his new skipper – Cephise nuspesez ( pronounced “new species” ). Just to prove that weird humour is not confined to entomologists, here are some of the equally odd scientific names given to other creatures :

| Abra cadabra | a species of clam – with magical properties ? |

| Agra vation | an “aggravating” carabid beetle |

| Cyclocephala nodanotherwon | a species of scarab beetle – “not another one !” |

| Heerz lukenatcha | a species of braconid wasp – “here’s lookin’ at ya !” |

| Kamera lens | a protozoan – shaped like a “camera lens” |

| Pulchrapollia | an extinct parrot, translates as “Pretty Polly” |

The above show both creativity and humor, but in 1969 when Spencer had the task of inventing names for new flies, he invented possibly the most boring series of species names in existence, by naming his discoveries sequentially, as **Ophiomyia prima,** **secunda,** **tertia,** **quarta,** **quinta,** **sexta,** **septima,** **octava,** **nona,** **undecima,** and **duodecima** (Latin for “first,” “second,” “third,” etc.). Dybowski went to the opposite extreme when he proposed the ludicrously unpronounceable name **Gammaracanthuskytodermogammarus loricatobaicalensis** for a new Amphipod in 1927. It would have been the world’s longest scientific name, but luckily common sense prevailed and the name was rejected by the International Commission for Zoological Nomenclature. The honor of having the longest scientific name actually approved by the ICZN goes to a species of Stratiomyid fly – Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides.

The shortest appears to be that of a Vespertilionid bat – Ia io, although there is a thrip with a single-letter species name – Plesiothrips o !