Danaus plexippus, USA – Frank Model

The images of Danaus plexippus photographed by Ingo Arndt that were originally posted here were supplied to us by Papadakis publishing with written permission for their free usage on this website.

The photographer Ingo Arndt later contacted us apparently unaware that Papadakis had granted permission for their usage free of charge. This was explained to Arndt and accepted by him. Neither Papadakis or Arndt have at any time requested that the images be removed, and neither Papadakis or Arndt have requested payment.

In January 2016 Minden Pictures demanded their removal and are currently threatening to impose a charge of GBP1420.00 for the past usage of these images. we dispute liability as free usage was explicitly given by Papadakis on behalf of their client Ingo Arndt.

Introduction

The Monarch is the most famous migrant in the butterfly world. Its powers of migration are so great that it has been able to spread to across the Americas from Canada to Peru. The first known record outside of America was of 3 specimens which crossed the Atlantic and were seen in Britain in 1876. Since then the Monarch has spread to north Africa, Europe and even to India. It has also crossed the Pacific ocean, reaching Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea.

In North America millions of Monarchs migrate annually over a distance of 2000 miles ( 3200km ) between their breeding territories in Canada and their southern over-wintering grounds in Mexico. Tagging of individual butterflies has proven that they regularly cover distances of up to 1100 miles in just a few days.

Each autumn as the climate cools in North America, vast numbers fly south, channeling into a few forested areas in the Mexican Highlands. During the winter months, fir trees in the tiny El Rosario sanctuary become festooned with millions of Monarchs. They totally cover the leaves, branches and trunks, sometimes even causing trees to fall under their weight.

| It has been estimated that an incredible 800 million Monarchs were present in the reserve in the mid-1990’s, but numbers dropped to about 100 million in 2004. The reasons for the variation are partly climatic, but the collapse is mainly attributable to illegal logging in the reserve. |

In February & March they awaken from hibernation and the air becomes a swirling mass of orange and black as tens of thousands of Monarchs take to the air. As the days get warmer they start to filter out of the sanctuaries and begin their return journey northwards. The females pause to lay eggs as they travel, creating temporary colonies along the route. The progeny also migrate north, laying their own eggs. Most of the original butterflies probably perish during the return journey, but there is evidence to show that some manage to return to the original breeding areas in the north.

It is little known that these amazing butterflies also regularly overwinter in small numbers in arid desert locations such as Saline valley in California – a moon-crater shaped valley about midway between Mount Whitney and Death Valley in the Mojave Desert. Monarchs regularly survive the winter there despite the very low daytime humidity ( 5-25% ), scant winter rainfall and the fact the only evergreen vegetation in mid and late winter are bushes such as tamarisk, mulefat and creosote. One problem with the Saline Valley habitats however is that once every five years or so, overnight temperatures drop several degrees below zero, and freeze most or all of the Monarchs.

The Monarch’s annual migration is controlled by a “time-compensated sun compass” that depends on light receptors and a circadian clock, both built into the antennae. When scientists removed the antennae from one group of Monarchs they flew strongly but in random directions, but a control group with their antennae intact all flew in the same direction – i.e. their south-westerly migration route.

In another experiment the antennae of some were painted with black enamel, and these butterflies when placed in a flight simulator all flew together, but in the “wrong” direction compared to their normal migration route. Another group had their antennae painted with transparent paint, and these all migrated together in the right direction.

| A circadian clock employs rhythms of biochemical, physiological or behavioural processes that control time based functions. These include daily activities e.g. the mate location / rest / feeding cycle of males, and the oviposition / rest / feeding cycle of females. The clock also influences or controls one-off activities such as emergence and migration. The precise timings are modified by environmental factors e.g. sunlight, rain and temperature. |

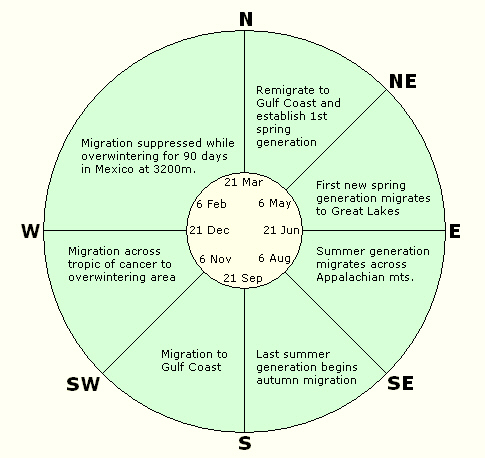

Insects do not “know” where they are, so cannot navigate by landmarks. They navigate primarily by using an internal compass in combination with a circadian clock which determines the timing of migrations. Monarch migration shifts clockwise at a rate of 1 degree per day for all generations of the annual migratory cycle. Northward migration from the overwintering site in Mexico is triggered by the spring equinox. Migration routes and speeds are of course influenced strongly by winds and weather conditions.

Diagram illustrating Monarch migration hypothesis:

|

Although Monarchs in North America are migratory in behaviour, there are also non-migratory populations which breed all year round in Central America, and on islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Research by Altizer has shown that the migratory subspecies have evolved wings which are about 14% larger in wingspan than those of non-migratory subspecies, presumably to allow them to travel vast distances with greater ease. Breeding experiments proved that these size differences are inherited, rather than being influenced by environmental factors such as warmer temperatures.

Habitats

Because of its migratory nature the Monarch can be found in virtually any habitat including prairies, grasslands, deciduous temperate forest, montane coniferous forest, subtropical rainforest, coastal habitats, deserts, parks, gardens, cities etc. It can be found at elevations between sea-level and at least 3400 metres. The butterflies can also be seen out at sea, and often settle on ships.

Monarchs will breed almost anywhere where the larval foodplants are available, typically in fields, meadows, forest glades and roadside habitats at elevations between sea level and about 1000m.

Lifecycle

The egg is shaped like a tall dome, straw coloured, and covered in vertical keels, each linked by numerous small horizontal ridges. It is laid singly on the underside of leaves of the foodplants which are almost invariably Asclepias but also include Calotropis ( Apocynaceae ).The caterpillar when fully grown is white, with each segment marked with narrow black and yellow vertical bands. The 2nd thoracic segment and 8th abdominal segment each bear a pair of black whip-like protuberances. Caterpillars are often parasitised by a tachinid fly Lesperia archippivora.

The larval foodplants Asclepias contain cardenolides – toxins which can induce cardiac arrest in small vertebrates. The toxins are sequestered by the caterpillars, and passed on to the adult butterflies which utilize them for defence against insectivorous birds, reptiles and rodents.

The pale green chrysalis is plump and barrel-shaped, with the abdominal segments compressed, forming a dome. At its widest point there is a narrow abdominal band studded with yellow and black dots. The chrysalis is suspended by a stout cremaster from stems on or near the foodplants.

Adult behaviour

The butterflies have a powerful but fluttering flight, interspersed with periods of soaring and gliding in wide circles as they fly from one clump of flowers to another. They settle frequently to nectar at Asclepias, Aster, Cirsium, Dispacus, Solidago, Syringa and Vernonia.

Courtship takes place in late morning at which time the male pursues the female in flight, nudging and cajoling her until she settles, typically on a bush, where copulation takes place.

The bodies of Monarchs contain cardenolides derived from the caterpillar’s foodplant Asclepias. Any bird eating a Monarch is likely to be affected by vomiting, muscular spasms and visual disturbance. Birds have the ability to learn and remember the patterns and colours of toxic butterflies, so after suffering the unpleasant experience of eating one Monarch they are unlikely to attack another.

Some birds however have learnt how to overcome the butterfly’s toxic defences, e.g. black-backed orioles Icterus abeillei have discovered how to strip out the body contents of Monarchs and discard the toxic elements. At one of the overwintering sites at Michoacan in Mexico it was estimated that between 3500-35000 Monarchs were eaten every day during the 1978-79 winter by black-backed orioles. Total mortality resulting from attacks by black-backed orioles and black-headed grosbeaks Pheucticus melanocephalus has been estimated at 1.8 million Monarchs per year at Michoacan.

As is the case with most toxic or unpalatable butterflies, Monarchs are involved in mimicry rings whereby several species, some toxic and some palatable, share a common pattern – in this case orange wings with black veins and white spots. Because they recognise and remember the patterns they are fooled into rejecting the palatable species due to their similarity to the toxic Monarchs.

The most well known mimic is the Viceroy Limenitis archippus, which for many years was thought to be a palatable species, and was therefore regarded to be a Batesian mimic of the Monarch. It is now generally accepted that things are not that clear cut – the degree of palatability encompasses a broad spectrum from species to species, and between individuals of any given species.

Limenitis archippus – Benny Mazur