Parasitoids

All stages of the lifecycle are threatened by parasitoids : creatures that feed on other organisms, and ultimately bring about their death. Note that parasitoids shouldn’t be confused with parasites – which unlike parasitoids do NOT bring about the death of their hosts.

Egg parasitoids

Many butterfly species fall victim to tiny wasps that inject their eggs into the soft newly laid butterfly eggs. When the wasp grubs hatch they feed on the organic matter within the egg, killing the potential caterpillar. The adult wasps emerge a few days later and use their mandibles to cut minute exit holes to make their escape from the eggs. In some cases as many as 60 microscopic wasps can emerge from a single butterfly egg.

South American Caligo Owl butterflies are parasitised by a tiny Trichogrammatid wasp that rides from place to place on the hindwings of female butterflies. When the butterfly settles momentarily to lay her eggs the wasp hops off, injects it’s own eggs into those of the butterfly, and then hops back onto the butterfly’s wing in time to be transported to the next egg laying site !

Caterpillar parasitoids

Throughout their lives caterpillars are very vulnerable to attack from parasitoids. Studies in Britain have revealed that with most Lepidoptera species, about 80% of larvae are attacked by parasitoid wasps or flies. In the case of the Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia between 90-95% of larvae are parasitised by the wasp Apanteles bignelli in certain years.

Wasps such as Apanteles, Amblyteles, Netelia, Ophion, Protichneumon and Ichneumon, and flies suchs Tachina, Gymnochaeta and Gonia spend their larval stage within the bodies of caterpillars.

The adult wasps and flies inject their eggs into the caterpillar’s body by means of a long sting-like ovipositor, or in some cases lay their eggs on leaves which are ingested by the caterpillar.

Hawkmoth larva Eumorpha fasciatus, Peru – Adrian Hoskins

The larva of Eumorpha fasciatus illustrated above has been parasitised by a wasp that injected it’s eggs into it. When the wasp grubs are fully grown they break out through the skin of the larva and form their papery white cocoons. The larva shrivels and dies. A few days or weeks later the adult wasps emerge from the cocoons and search for another larva to parasitise.

The larva of Hasora badra shown below has been parasitised by an Apanteles species – a total of 67 wasps emerged from the cocoons which surround it.

Common Awl Skipper Hasora badra surrounded by Apanteles cocoons – SoonChye

Defence strategies

( see also Larval survival mechanisms )Many larvae are equipped with thick coats of hair, or fierce-looking spikes that make it difficult for parasitoids to settle on them. Others, e.g. those of the Puss moth Cerura vinula and the hawkmoth Isognathus leachi are armed with long whip-like structures which they use to drive off any wasp or fly that attempts to attack.

Isognathus leachi, Fazenda Rancho Grande, Rondonia, Brazil � Adrian Hoskins

Unfortunately in practice it the whip is not very effective as a defence, as Paul Bertner describes :”We spotted the Winthemia tachinid fly circling around the Isognathus larva. The extremely long tail of the larva appears to serve a defensive function.

As the fly landed close to the rear, the larva would flick its tail, dislodging the fly to prevent it from ovipositing. The fly undeterred walked up the body until it was close to the head and out of range of the tail where it began to lay eggs. It seemed to prefer the posterior end of the larva for some reason as it kept on trying to move back there, perhaps laying too close to the front might kill the larva faster and thereby not leave enough time for the fly grubs to mature, whereas the rear of the larva may not house such vital organs to be destroyed by the grubs”.

The long orange ovipositor of the fly can be seen quite clearly in the photo below :

Tachinid fly Winthemia sp, injecting eggs into an Isognathus larva – Paul Bertner

Some flies such as Sturmia bella don’t oviposit directly on the larva. Instead they lay their eggs on its foodplants. These are ingested and pass into the larva’s gut. After the eggs hatch the resulting grubs consume the larva’s flesh, but leave the vital organs alone, allowing the larva to continue to live and grow. Eventually when the parasitoid grubs are mature and ready to pupate they eat the vital organs. They then pupate either within the body of the dying larva, or eat their way out of it’s skin and pupate externally.

Nematode worms

The larvae of many butterflies and moths are attacked by entomopathogenic nematode worms from the family Mermithidae. The tiny juvenile worm is sometimes unintentionally ingested by a larva as it browses on leaves. In other cases it may enter via the larva’s anus. The larva depicted below is that of Cyclosia papilionaris – a moth in the family Zygaenidae. It has been parasitised by a single Mermethid worm which has fed and grown within it for several days. When the worm is fully grown it exits the larva, which shrivels and dies.

Cyclosia papilionaris with parasitic worm, Cambodia – Dani Jump

Parasitoids of pupae

Other wasps attack newly formed butterfly pupae while the skin is still soft and easily punctured. An example is the beautiful metallic green wasp Pteromalus puparum, which attacks pre-pupal larvae and newly formed pupae of Pieris brassicae. The entire lifecycle of Pteromalus takes place within the butterfly pupa, and the tiny wasps emerge in dozens after making exit holes in the pupal skin.

The pupae of many Lycaenidae species are attended by ants ( see myrmecophily ). The presence of ants is beneficial to the pupae because ants drive away predatory insects and parasitoid wasps that would otherwise attack them. Experiments with the Australian hairstreak Jalmenus evagoras for example have shown that in cases where ants have been denied access to the pupae the latter have suffered up to 95% parasitism by the wasp Brachymeria reginia. Conversely, pupae attended by the ants experienced zero parasitism.

Parasites

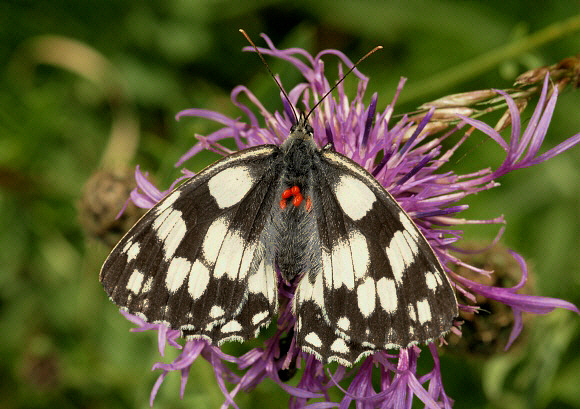

Parasites are creatures which feed upon other organisms, but unlike parasitoids they do not cause the death of their hosts. In the case of Lepidoptera, they generally affect the adult butterflies and moths rather than caterpillars.Certain butterflies, particularly males of Meadow Brown Maniola jurtina, Marbled White Melanargia galathea, Common Blue Polyommatus icarus & Small Skipper Thymelicus sylvestris are commonly parasitised by tiny red mites Trombidium breei, which normally attach themselves to the thorax or legs of the butterfly. They transfer from host to host when the butterflies alight to nectar at flowers.

Melanargia galathea with parasitic red mites Trombidium breei attached to thorax – Adrian Hoskins

Studies have shown that the Trombidium mites have no detectable effect on the flight performance, orientation ability or lifespan of the butterflies. In New Zealand however there is another species of mite called Dicrocheles, which does have an injurious affect on adult Noctuid moths. They infest the “ears” on the wings of the moths. Apparently, in areas where there are no predatory bats, the mites attack both ears, making the moths go completely deaf. But in areas where bats thrive, the mites seem to only attack one of the ears, so the moth is still able to detect the bat’s acoustic pulses and take avoiding action. The theory goes that “if the moth cannot hear the bat, both the moth and the mites will almost certainly be eaten, so they make sure to keep one ear functional”.

In South American cloudforests, adult Glasswing butterflies Greta andromica, are often attacked by Ceratopogonid midges, which feed on the blood in the butterfly’s wing veins and eyes. The same midges also attack larvae, sucking their haemolymph.

Pseudoscorpion hitch-hikers

Close examination of recently emerged butterflies can sometimes reveal the presence of very tiny scorpion-like creatures clinging by their pincers to the legs or antennae. These “pseudoscorpions” are carnivorous, typically feeding on mites, insect eggs and young larvae, but don’t harm the butterflies. They simply hitch a lift on butterflies and other insects, using them as transportation to enable them to disperse to new habitats.

One tactic they use is to ambush a fully grown caterpillar, grabbing its spines or head horns with their powerful pincers. When the pincers “bite”, the pseudoscorpion becomes quiescent. After a few hours the caterpillar pupates, and the pseudoscorpion remains attached to the shed larval skin, which itself remains attached to the base of the pupa. Eventually the butterfly emerges from the pupa, and the pseudoscorpion then scuttles on board, grabbing hold of its antennae or legs. This causes the butterfly to take flight. Sometime later, when the butterfly lands in a suitable place, the pseudoscorpion drops off, and colonises it’s new found habitat. Pseudoscorpions are related to spiders, mites, scorpions and harvestmen. Their hitch-hiking behaviour is known as “phoresy”.

Pathogens etc

Fungal and viral diseases are most prevalent in cool damp conditions and cause the death of many hibernating larvae and pupae in temperate regions. They also affect the early stages of tropical species, particularly during the rainy season. Living caterpillars are subject to infection by many fungi including Cordyceps, Metarrhizium and Beauvaria.

Caterpillars are often attacked by nuclear polyhedrosis viruses, granulosis viruses and cytoplasmic polyhedrosis viruses. Affected larvae become limp, darken in colouration, and produce liquid faeces prior to death. The condition is known as wilt disease, and is highly infectious.

The larva illustrated below may look as if it is dead and going mouldy but in fact it was very much alive, crawling rapidly over the leaves of a small bush deep in the Amazonian rainforest. The larva has been infected by an entomophagous fungus. Its rapid movement is an example of how normal behaviour is altered in an infected host. Some entomologists speculate that this type of behavioural change is a self-sacrifice survival technique, whereby an individual that is doomed to die will draw attention to itself and in doing so divert the attention of predators away from its healthy and slower moving cogeners. Whether insects are capable of such altruistic acts is of course debatable!

unidentified moth larva ( ref 016 ), Rio Madre de Dios, 400m, Peru – Adrian Hoskins

Despite the massive losses ascribable to predators, parasitoids, viral / fungal diseases and physical causes ( rain washing away eggs, caterpillars falling from their foodplants etc ), enough offspring generally survive to maintain reasonably stable populations.

The Balance of Nature

Invertebrate predators possess varying degrees of intelligence and quickly learn how to overcome the huge variety of defence mechanisms employed by their prey. It is known that some birds can pass on learnt behaviour to their offspring, so their ability to locate and butterflies and their larvae increases with each passing generation. Many birds also possess empathic learning abilities, so an individual can learn to avoid toxic butterflies simply by observing another bird vomiting or suffering muscular spasms after regurgitating one.

Luckily butterflies have a couple of advantages over birds. Firstly, a high percentage of species are polyvoltine ( producing several generations per year ). This rapid rate of reproduction allows them to recover their numbers rapidly even after major losses of population. Secondly, butterflies and moths intrinsically produce high genetic diversity. These two factors result in an ability to evolve rapidly, the consequence being that the battle between birds and butterflies has become a closely run race. Birds catch enough caterpillars and butterflies to feed themselves and their offspring, but at the same time enough butterflies survive to ensure that both predator and prey can continue to co-exist. This is the so-called “balance of nature”, an ongoing evolutionary battle between predator ( or parasitoid ) and prey.

Short term variations in this balance are mainly attributable to seasonal fluctuations in climate :Caterpillars are cold-blooded, and need warmth to induce feeding activity. Thus in a cool spring they take longer to develop, so more get eaten by birds, and more get attacked by parasitoids. In the case of nocturnal larvae the opposite is the case – cloudy weather stops night temperatures from dropping and increases the caterpillar’s growth rate. So in poor weather they develop more rapidly and fewer get attacked by parasitoids.