Abundance & diversity

It is difficult for someone born and raised in the northern hemisphere to comprehend the incredible diversity and abundance of butterflies in the tropics. In Britain e.g. a butterfly enthusiast exploring a 1000 hectare / 4 square mile mosaic of deciduous forest and chalk grassland would be considered lucky to see 30 species in an entire year. In Peru, Brazil or Ecuador however you would be justified in considering yourself unfortunate if you saw less than 600 species in a similar sized area – and you would probably be able to see well over 300 in a single week.

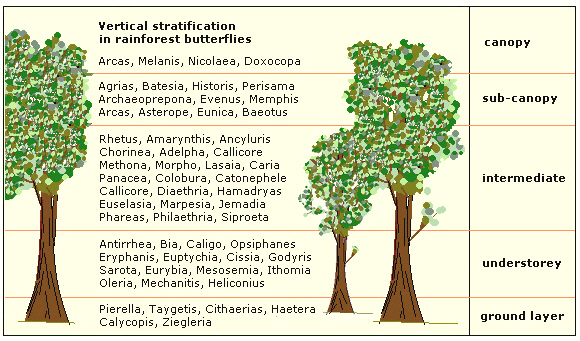

The great diversity of butterflies in the tropics is largely due to the extraordinary range of climatic conditions and the huge variety of different habitats, which include rainforests, cloudforests, heaths, grasslands and deserts, each comprising of many sub-habitats. Together these create an enormous array of ecological niches in which species can exist and evolve. In rainforest e.g. some butterflies such as Doxocopa and Arcas live high in the tree tops, but most Satyrines and Ithomiines spend all their lives in the understorey or at ground level.

The diagram below gives an indication of the butterfly genera associated with various layers within a rainforest. It should not be interpreted too literally – the males of many tree-top dwelling species such as Melanis, Doxocopa and Perisama commonly descend to ground level to imbibe mineralised moisture. Also, in places where trees have fallen, shafts of sunlight penetrate, creating “light gaps” which encourage many other species to descend to lower levels.

Other factors contributing to the great diversity of butterflies are the hot climate and the evergreen nature of the foliage in the tropics. These enable several generations to breed each year – as many as 10 generations for some species, compared with just one or two in temperate regions. This rapid rate of reproduction provides many more opportunities for mutations to arise, and for new species to evolve.

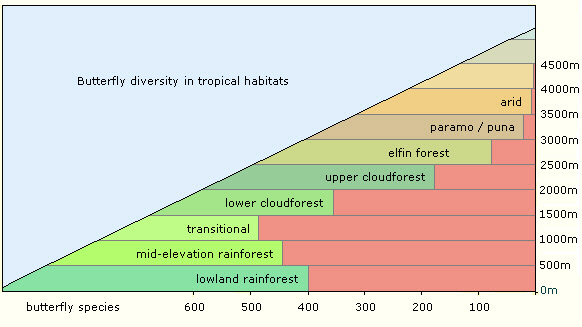

The diagram above gives a very rough indication of the total number of different butterfly species which can be found at various altitudes in the eastern Andes. As can be seen, at about 500m there are typically around 400 species. This generally increases to a maximum of about 500 at 1500m and then decreases with rising altitude until there are only about 50 species at 3000m. The diagram is only intended as a rough guide – the actual number of species is governed by geographical location and numerous other factors.

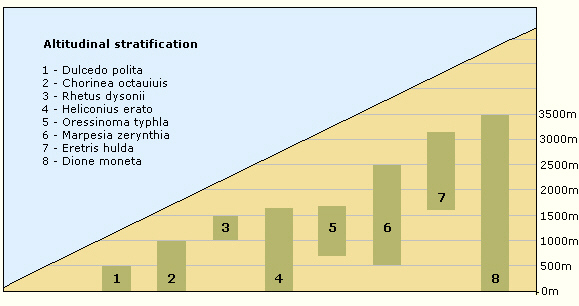

Some species have a very restricted altitudinal range e.g. Dulcedo polita is only found below 400m; and Rhetus dysonii is restricted to a belt between 1000-1500m. There are several Satyrine genera that are restricted to the cloudforest / grassland transition zone between about 2800-3200m. These include Pedaliodes, Lymanopoda, Eretris and Steroma. A very small number of species e.g. Dione moneta and Hylephila phyleus are able to exist across the whole spectrum of altitudes and habitats from 0-3500m. The vast majority of tropical butterflies however are found only between 0-1500m, as shown in the diagram below.

Seasonality

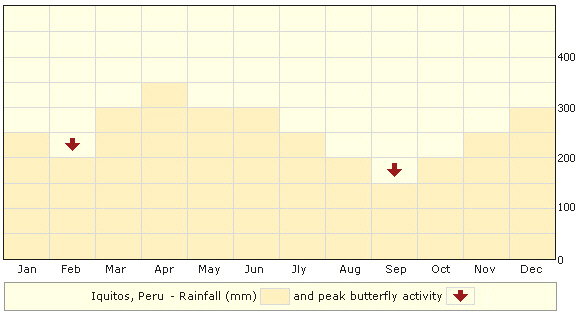

There is a popular misconception that butterflies can be found in equal abundance at all times of the year in the tropics. It’s true that seasonality is far less pronounced than in temperate regions of the world, but nevertheless most areas experience distinct wet and dry seasons which have a major impact on diversity and abundance.

Deciduous forests and grasslands

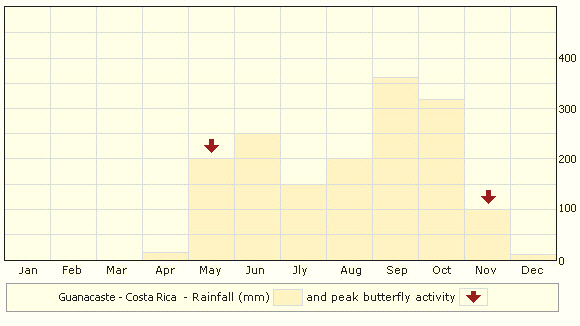

In deciduous regions such as Guanacaste in Costa Rica butterflies are far more abundant in the wet season. During the dry season they are scarce and hide away deep in the forest where they gather at damp gullies and riverbeds. About 3-4 weeks after the first rains, butterflies suddenly emerge en masse. First to emerge are usually the Ithomiines, Morphos and Satyrines. The Riodinidae, Pieridae, Papilionidae, Melitaeinae, Apaturinae and Hesperiidae tend to follow a few weeks later, peaking in July. The Lycaenidae are usually the last to emerge.

The total number of species found in the deciduous regions is small compared to those in rainforests and cloudforests largely because deciduous forests only support a small number of Ithomiines – and consequently there are far fewer Mullerian and Batesian mimic species.

The weather systems that control seasonality are complex. Generally speaking, in Central America and the southern Amazon, both of which are a considerable distance from the equator, seasonality is very pronounced. There may be long periods of drought, while at other times of year it rains for several hours every day. In Ecuador, Peru and the northern Amazon, all of which are much closer to the equator, seasonality is less extreme.

In these areas it rains periodically even during the dry season. Consequently butterfly abundance is more even throughout the year. Nevertheless there are population peaks and troughs, because butterflies try to time their emergence to ensure that their foodplants have fresh young leaves at the time when their larvae hatch.

In both Central and South America the presence of huge mountain ranges has a dramatic affect on climate and on butterfly populations. When the winds are blowing from the west, the western slopes of the Andes receive high rainfall but the eastern slopes and the upper Amazon are dry. When the winds are blowing from the east the situation is reversed. During El Nino years however changes in ocean and air currents cause the seasons to reverse.

In areas where the seasonality is extreme, many species produce dry and wet season forms which differ in colour and even in shape. Dry season forms tend to have cryptic “dead-leaf” patterns and colours to camouflage them as they rest among dead brown and yellow leaves. Wet season morphs on the other hand are usually darker with more contrasting patterns and rounder wings.