Population control in nature

Strictly speaking, predators and parasitoids should not be considered as enemies of butterflies. They could perhaps instead be thought of as Nature’s way of preventing butterfly populations from getting out of control – if they were not kept in check, the populations would rapidly expand and would quickly deplete all available food resources, ultimately leading to their own demise.

A butterfly may be capable of laying up to 500 eggs. On average however only about 100 will be laid, as many females die before they are able to lay all their eggs. Perhaps 95 of those eggs will hatch. 85 of the resulting caterpillars are likely to be killed by birds, wasps, spiders or parasitoids, leaving just 10 to reach pupation. Studies have found that over half of all wild pupae will be eaten, be killed by parasitoids, or die from desiccation, fungal attack, or other causes.

The net result is that the eggs laid by a single butterfly will, averaged over several years, result in only about 4 adults per generation. As many as half of the adult butterflies will be killed before they mate or are able to lay eggs. So, despite the ability to produce those 500 eggs and the potential of 500 butterflies, just 2 butterflies will result from each brood of eggs. With luck one of these will be a male and the other a female, and another batch of eggs will be produced.

Avian predators

Throughout the world, adult butterflies are killed in vast numbers by birds including sparrows, tits, thrushes, robins, orioles, jays, grosbeaks, crossbills, flycatchers, jays, tanagers and jacamars.Various studies have provided statistical data on avian predation. One study for example revealed that 160 out of 697 examined specimens ( 23% ) of Ascia monuste bore beak marks on their wings indicating that they had been attacked by birds, but had escaped or been rejected. This figure does not of course include the specimens that were actually eaten.

Another study of the feeding behaviour of ( captive ) rufous-tailed jacamars Galbula ruficauda in Costa Rica found that when 1679 butterflies of 133 species were offered to the birds approximately 5% were classed as failed attacks. 35% were ignored or sight-rejected. About 20% were attacked, captured and then taste-rejected. The remaining 40% were attacked, killed and eaten. The species offered to the birds were categorised according to colour. Those that were sight-rejected or taste-rejected generally were aposematically coloured species, while those that were devoured tended to be the less colourful or cryptically patterned butterflies.

It is apparent from the many studies carried out that at least 50% of wild butterflies are killed and eaten before they are able to mate and reproduce. Some are attacked when they are emerging or drying their wings prior to their first flight. Others fall victim when basking on the ground or visiting flowers, although many are lucky to escape with nothing more than a peck taken out of a wing.

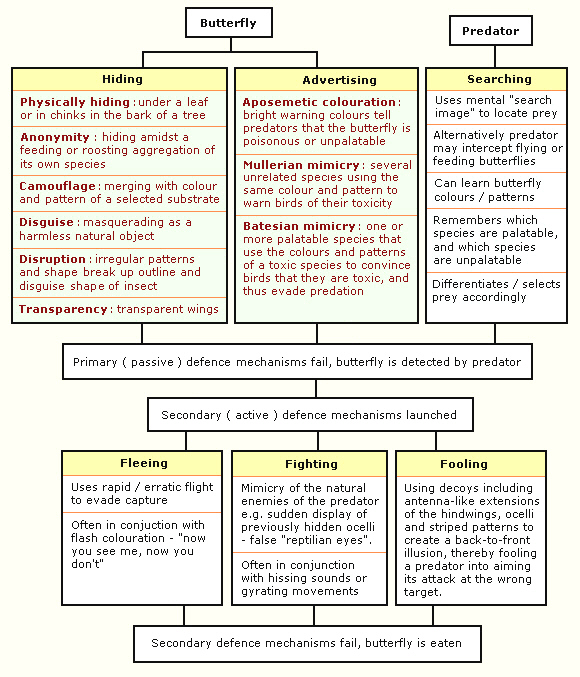

Birds and other vertebrate predators rely primarily on sight to locate prey, so butterflies and moths have evolved numerous visually mediated means to avoid attack. These include passive defence mechanisms e.g. camouflage, disguise, mimicry, warning colouration and transparency. Sometimes passive mechanisms fail, and a butterfly will find itself under direct attack. At this stage secondary or active mechanisms come into play.

The flowchart below illustrates many of the survival strategies which butterflies have evolved to defend themselves against attacks by insectivorous birds :

Spiders and predatory insects

Although birds are probably the main predators, adult butterflies also have to contend with spiders, wasps, dragonflies, robber flies and crickets. In warm climates they are also attacked by mantises and numerous other arthropods.

It is common to see butterflies caught in the grip of crab spiders, which lie in wait among flowers, ambushing any butterflies that visit them for nectar. Butterflies also often wander into the webs of orb spiders. The smaller weaker butterflies such as Polyommatus, Lysandra and Coenonympha invariably become entangled and are quickly wrapped up in silk for later consumption. Larger butterflies however such as Vanessa and Argynnis are often able to struggle free before being pounced upon by the owner of the web.

Close examination of adult butterflies often reveals a give-away reticulation pattern across the wings, marking the places where loose wing scales have become detached and left behind on the sticky threads of the web. It is even possible that wing scales have evolved to be easily detachable as a survival mechanism.

Hornets and wasps are major predators of butterflies in mid-late summer. By way of example, in July 2009 at Alice Holt forest in England I watched a hornet Vespa crabro chasing after Ringlets and Meadow Browns. It failed to catch any, but moments later, when I was trying to photograph a White Admiral nectaring at bramble, another hornet suddenly shot down and snatched the butterfly from the flower. In a split second it had grabbed it, bitten off its forewings, and used its hindwings to wrap the paralysed butterfly up into a tight ball. Seconds later, carrying the parcel in it’s mandibles, it flew up to its nest at the top of a small oak. Once there it would have chewed the butterfly into a pulp and regurgitated it to feed its developing grubs – adult hornets are strictly vegetarian, feeding on nectar and fruit.

|

Broad-bodied Chaser Dragonfly Libellula depressa commonly preys on butterflies – Adrian Hoskins

In southern Britain one of the commonest butterfly predators is the spider Enoplognatha ovata, a member of the Theridiidae. This small species traps summer butterflies which fly into the sticky strands of an untidy web which it spins on grass-heads and wild flowers. I made a brief study of predation at Magdalen Hill Down in Hampshire in July 2009 and estimated that about 5% of the population of Chalkhill Blues Lysandra coridon fell victim to this spider.

|

| Theridiid spider Enoplognatha ovata, devouring Chalkhill Blue Lysandra coridon – Adrian Hoskins |

|

| Hunting spider Pisaura mirabilis – Adrian Hoskins |

Male hunting spiders Pisaura mirabilis attack butterflies that settle on low herbage. They wrap their victims tightly in silk and present them to the female spider as a courtship gift. While the spiders are mating the female feeds on the butterfly.

Crab spiders are a major predator of small butterflies. An individual will sometimes spend several days sitting motionless on a flower head, waiting it’s next victim to fly in. The peripheral vision of the spider is poor, so much so that it is possible for a butterfly to settle alongside it without being noticed. If on the other hand it is unfortunate enough to walk across the spider’s field of forward vision, the arachnid will move immediately and stealthily towards the butterfly and seize it with its powerful pincer-like forelegs. The spider then bites the butterfly on the neck, injecting it with a paralysing venom which incorporates enzymes that liquefy the victim’s internal tissues.

The photo below illustrates a Chestnut Heath Coenonympha glycerion that has been ambushed by the crab spider Thomisus onustus.

This remarkable spider has a chameleon-like ability to change colour to match it’s surroundings. It can be white, yellow, pink or variegated in appearance. The change of colour takes about 2 or 3 days to complete however, so it’s common to find a spider on the “wrong” coloured flower.

|

| Coenonympha glycerion, ambushed by crab spider Thomisus onustus – Peter Bruce-Jones |

|

| Altinote dicaeus attacked and eaten by a cricket in Manu cloudforest, Peru – Adrian Hoskins |

Predators of caterpillars

Butterfly and moth larvae are taken in huge numbers by predators. A study of predation on Pieris rapae estimated that 52% and 63% of 1st / 2nd instar larvae were eaten in 2 consecutive years by invertebrate predators including Carabid beetles, Hemipteran bugs, wasps, mites and spiders. The same study estimated that as many as 22% of older Pieris rapae larvae were taken by birds, which of course have to feed not only themselves but their offspring at the nest.

Birds, reptiles, amphibians and small mammals rely primarily on sight to locate prey. Lepidopteran larvae have correspondingly evolved a battery of visually directed defence mechanisms to reduce the likelihood of being eaten. These include camouflage, disguise, mimicry, aposematic / diematic colouration and the use of stinging spines to ward off attacks.

These strategies work quite effectively against vertebrates but they provide no protection against invertebrates such as spiders, wasps, bugs and ants, which rely primarily on smell to locate their prey. The larvae of many species have consequently evolved alternative solutions. The larva of the Puss moth Cerura vinula for example is armed with long “tail whips”. If attacked it arches it’s body into an aggressive posture and uses the whips to thrash the attacker to drive it away.

Swallowtail larvae are palatable to birds and employ cryptic colours and patterns as a first line of defence. If discovered however they activate secondary defences. Many of them are marked with a pair of “false eyes” on the thoracic segments, so they inhale air through the spiracles and puff up these segments to emphasise their threatening appearance. This is often enough to deter avian and reptilian predators. Molestation by insect predators and parasitoids elicits a different response from the larvae. In this instance they evert a fleshy structure behind their heads called an osmaterium. This discharges airborne isobutyric and 2-methylbutyric acids which has been shown to repel ants and Homopteran predators. It also deters oviposition by parasitoid wasps and flies.

The larvae of species such as the Peacock butterfly Inachis io, the Tiger moth Arctia caja and the Fox moth Macrothylacia rubi rely on escape tricks. If molested they simply roll into a ball and drop to the ground. Geometrid moth larvae use disguise as their primary defence – they look just like tiny twigs, and reinforce this similarity by stretching out their bodies in a straight line so that they project twig-like from a sprig of their foodplant. If they are molested they release grip on the sprig and drop instantly from a bungee-cord of silk. They dangle at the end of this until the attacker has moved on. After a while they haul themselves back up, consuming the silk thread as they does so.

The larvae of many members of the family Lycaenidae defend themselves by forming a beneficial association with ants. The anal segment of the larva houses a dorsal honey gland which exudes a sweet tasting fluid which ants love to drink. The larvae thus find themselves constantly attended by dozens of ants, the presence of which deters predators & parasitoids from attacking. Many species take the association a stage further and are carried by the ants into their nests where they feed on ant grubs, aphids or fungi. The ants don’t attack the larvae as the latter are able to mollify them, either by using chemical deterrents or by stridulating to produce an “appeasement song”. Research on several Hairstreaks and Blues in Europe has demonstrated that their larvae and pupae are able to generate an audible “chirp” which deters ants from attacking.

Caterpillar defence mechanisms are discussed more fully in the lifecycle section.

Heteropteran bugs such as this species from Peru often attack and eat larvae – Adrian Hoskins

Adders and other juvenile snakes eat diurnal butterfly and moth larvae, as well as beetles, spiders and nestling rodents. Click here for more about the Adder – Adrian Hoskins

Common Toads are major predators of European caterpillars such as Ringlet and Speckled Wood. Click here for more about the Common Toad – Adrian Hoskins